BIO

Biography

Steven Donziger never imagined, when he joined a legal team bringing suit against Chevron for polluting Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, that the case would take up a good portion of his life and define his career. Just two years out of Harvard Law School when the class action suit began, Donziger has spent decades on the legal battle to bring justice to the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. “I did not set out to be an environmental lawyer,” says Donziger. “I simply agreed to seek a remedy for 30,000 victims for the destruction of their lands and water; to seek care for the health impacts including birth defects, leukemia, and other cancers; and to help them restore their Amazon ecosystem and basic dignity.”

Steven Donziger never imagined, when he joined a legal team bringing suit against Chevron for polluting Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, that the case would take up a good portion of his life and define his career. Just two years out of Harvard Law School when the class action suit began, Donziger has spent decades on the legal battle to bring justice to the indigenous peoples of the Amazon. “I did not set out to be an environmental lawyer,” says Donziger. “I simply agreed to seek a remedy for 30,000 victims for the destruction of their lands and water; to seek care for the health impacts including birth defects, leukemia, and other cancers; and to help them restore their Amazon ecosystem and basic dignity.”

Donziger knew Chevron would fight the charges, “I did not, however, expect the lengths they would go to to attack me personally, attack my family, attack their victims, and defy a legal judgment that they pay for their crimes, as proven in a court of law.”

The problem started in 1964 when Texaco began drilling and mining large oil deposits in the Lago Agrio region of Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, the ancestral lands of the Cofán people. The company’s operations quickly transformed a remote region inhabited by indigenous farmers and laborers into an industrial zone. Using techniques banned in the United States, Texaco burned extra crude and dumped cancer-causing drilling muds into unlined pits. Pipes installed by the company ran the toxic contamination into streams and rivers relied on by local communities for their drinking water. Separation stations deposited wastewater full of petroleum, salt, heavy metals, and other toxins into the rainforest’s streams and rivers, devastating the region’s life-sustaining force. For decades the peoples watched their homeland, previously untouched by industrial civilization, suffer exploitation and degradation from a slow poisoning that touched almost every aspect of their lives.

Fish disappeared from local rivers. Game stock hunted by locals dwindled. Land became infertile. The region’s inhabitants, dependent on the rivers for drinking, bathing, and cooking water, developed skin rashes and other ailments. Miscarriages and birth defects became common. Cancer rates and deaths increased. Children and livestock that drank from or swam in the once-pristine waters died. Environmentalists nicknamed Lago Agrio the “Amazon Chernobyl.”

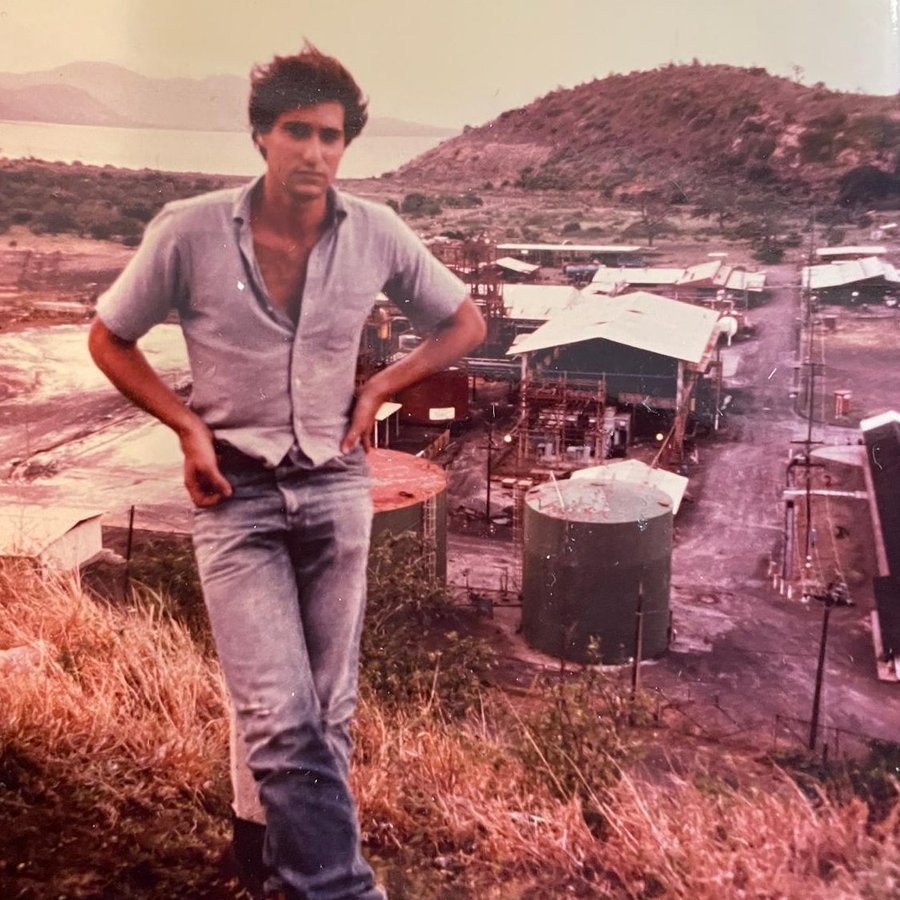

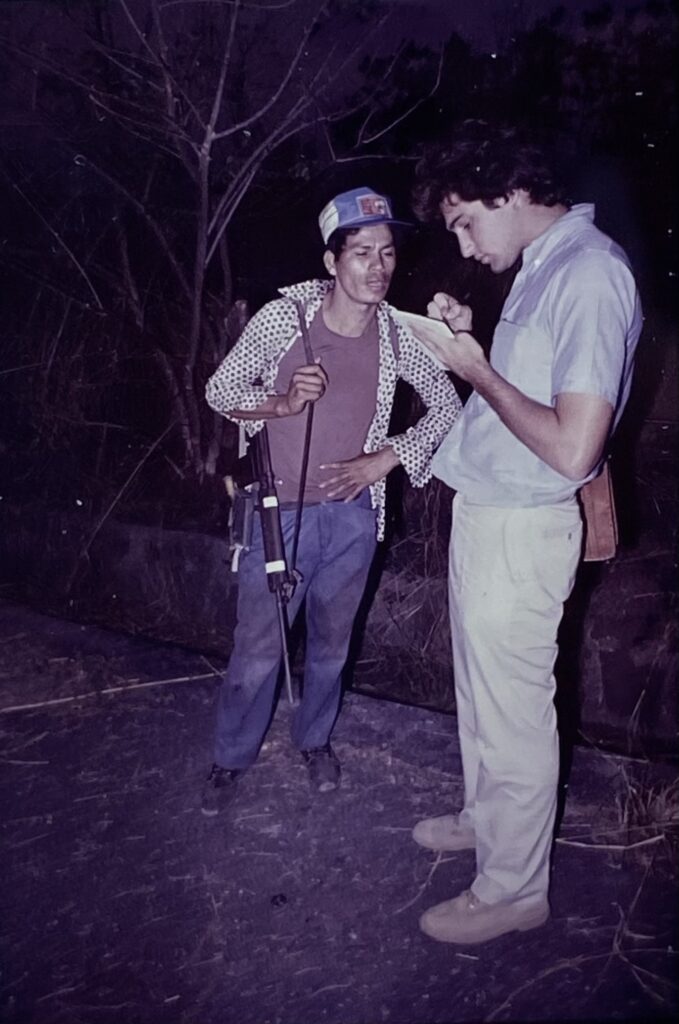

In 1993, Donziger traveled to Ecuador with a team of lawyers to investigate. They found “what looked like an apocalyptic environmental disaster in the rainforest.” Open waste pits throughout the rainforest. People drinking contaminated water. Oil on roads. Oil on people’s feet. “They treated the people as if they were playthings,” Donziger explained. “This was not an accident like you saw in the Gulf with the BP. It was clearly foreseeable that this deliberate dumping of billions of gallons of toxic waste would not only destroy the environment, but it would kill people.”

Ecuadoran-American attorney Cristóbal Bonifaz recruited Steven Donziger and other lawyers to help the affected communities in the Amazon to hold Texaco accountable. The first stage of the class-action suit, filed at the site of Texaco’s headquarters in New York, dragged on for nearly a decade. In 2001, Chevron purchased Texaco and assumed responsibility for the litigation.

Like many American multinationals, the company preferred a foreign judge to a U.S. jury. Chevron claimed, and the court agreed, that the case should be moved to Ecuador. Chevron accepted jurisdiction in Ecuador and agreed to pay any adverse judgment.

Like many American multinationals, the company preferred a foreign judge to a U.S. jury. Chevron claimed, and the court agreed, that the case should be moved to Ecuador. Chevron accepted jurisdiction in Ecuador and agreed to pay any adverse judgment.

The company’s gamble failed, and in 2011 an Ecuadoran court ordered Chevron to pay $18 billion to clean up the oil spill. The amount was later reduced to $9.5 billion. Chevron appealed. Eight high-court judges In Ecuador upheld the ruling. Chevron refused to honor the courts’ findings and instead removed its assets from the country. The company then used 60 law firms and 2,000 lawyers to wage a full-throttle legal attack on Donziger and his clients.

Alleging the Ecuadoran judgment had been obtained through bribery and fraud, Chevron filed a civil “racketeering” case before a federal court in New York and steered the case to a pro-business judge who was a former tobacco industry lawyer. Without a jury and after excluding scientific evidence of pollutants used to find Chevron liable in Ecuador, Judge Lewis A. Kaplan ruled in favor of Chevron. Kaplan, again without a jury, then imposed millions of dollars of cost orders on Donziger, a move seen by Donziger as an attempt to bankrupt him and drive him off the case. The “evidence” against Donziger was fabricated: it came from an admittedly corrupt witness paid $2 million by the company and coached by Chevron lawyers for 53 days before taking the stand. The witness later admitted lying.

Again using its favored judge Kaplan, Chevron sought further recrimination against Donziger, filing for access to his personal and professional assets, including his cell phone, computer, and all electronic accounts. Donziger refused to give Chevron this “near wholesale access to confidential, privileged, and protected documents, without any legitimate basis.” He appealed the order as an unconstitutional attack on attorney-client privilege. Judge Kaplan intervened, charging Donziger with criminal contempt of court. Kaplan and another judge he appointed, Loretta Preska, then ordered Donziger locked up in his house to await a trial that that was repeatedly delayed because of the COVID pandemic. To Donziger and several international law experts, this felt like a case of judicial and corporate harassment of the type often seen in authoritarian societies.

On August 6, 2019, Steven Donziger left a courthouse in lower Manhattan wearing a tracking bracelet on his ankle. His bond was $800,000, or higher than three of the four officers who killed George Floyd. He spent over eight hundred days under house arrest and over a month in federal prison. Then, in 2020, contrary to the recommendation of an independent referee, Donziger was disbarred from practicing in the State of New York.

In the meantime, the people of Ecuador’s Lago Agrio region suffer as unlined pits filled with crude oil and toxic waste continue to contaminate water and soil and destroy lives. Director of Amazon Watch Paul Paz y Miño calls Lago Agrio “a perfect example of environmental racism. There’s no way they would get away with doing this to white people in California. But indigenous and brown people in Ecuador, they can deliberately poison them, and never pay, and turn it around and blame them.”

“There is little doubt that Chevron’s ‘Amazon Chernobyl’ is the worst oil-related environmental and human rights disaster on the planet,” says Donziger. Yet while BP has paid out more than $65 billion for the Gulf of Mexico’s Deepwater Horizon oil spill, Chevron has paid nothing to compensate thousands of people for decades of egregious harm. The BP disaster in the Gulf of Mexico was an accident; Chevron’s pollution in Ecuador’s Amazon was part of a deliberate design.

Chevron’s extraordinary efforts to fight Donziger speak to the importance of the Ecuadoran ruling and its perceived threat to the oil industry’s profit model. This profit model depends on externalizing the costs of environmental harm, costs that fall mainly onto vulnerable indigenous peoples and rural communities. The model accelerates climate change and transfers responsibility for clean-up of pollution caused by the company to the public. Donziger explains, “The new corporate playbook is to turn the law into a weapon to attack the vulnerable, rather than be used as a shield to protect the vulnerable from abuse by the powerful.” If allowed to continue, and if the lawyers fighting this model are not protected by law, Chevron and the fossil fuel industry as a whole will continue pulling in profits at the expense of people’s lives and the health of the earth.

Steven Donziger never imagined, when he joined a legal team bringing suit against Chevron for polluting Ecuador’s Amazon rainforest, that the case would take up a good portion of his life and define his career.